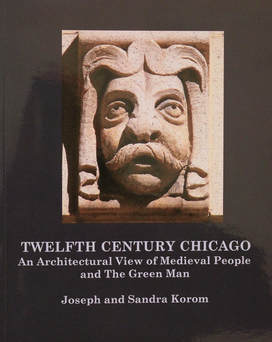

1) CLICK THIS IMAGE TO PREVIEW TWELFTH CENTURY CHICAGO

2) WHEN THE NEW PAGE APPEARS, CLICK TO PAGE THROUGH THE BOOK

2) WHEN THE NEW PAGE APPEARS, CLICK TO PAGE THROUGH THE BOOK

A tender townsman feeds

a flock of doves, traditional symbols of peace. Ironies abound in this

medieval-based image: This lute player (his instrument is thrown over his

shoulder) also possesses a sword and shield, weapons of war. His shield bears

an image of a caged bird while he attends to “free” birds. But these are more

than just birds; they are metaphors for serfs and freemen. The red-clothed

benefactor, the nobility, provides food, music, and protection to those lucky

to live as freemen in the city in the distance, while the land-based

laborers—farmers—remain “enslaved” by feudal tradition and law. Chicago’s architectural sculptures similarly

display much in the way of irony. Image c.1900. Hubert Kohler, lithographer, Munchen. Artist: Rudolph Schlestl, 1899. Collection

of the author.

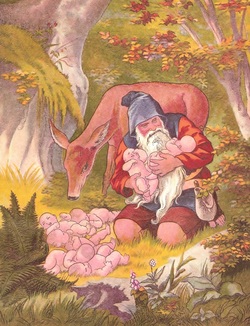

A forest rustic,

perhaps a benevolent dwarf or Green Man, cuddles babes in the woods. Chicago

children were familiar with such tales of mystery and adventure. Sometimes on

an outing, the young ones would see images on buildings that reminded them of

such stories of long ago and far away.

Image 1883. Hours in Fairy Land,

From Grimm, McLoughlin Brothers, New York. Copyright 1883. Collection of

the author.

Staring with piercing, haunting eyes and carved some thirty-five generations ago is this frightening fellow. This Renaissance-age Green Man appears upon an obscure terra cotta panel. Its location is most likely England or France and is included in this study as a comparative entry, a talisman from the Old World. Objects like these were referenced for New World buildings by New World architects inspired by Old World designs. Artworks similar to this one may be spotted on façades throughout Chicago. Image: c.1900. Collection of the author.

Hundreds of shields

similar to this one are visible throughout Chicago. Artfully composed of stone

or terra cotta, they remind citizens of medieval Europe—whether they wish to be

reminded or not. The shield’s fleur de lis

(lily flower in English) design has great significance and is also omnipresent.

The fleur de lis (with hundreds of

design variations) hails from the age of Charlemagne and has always been

associated with the monarchs of France. Its appeal resides in its colorful

political, religious, symbolic, and artistic history throughout the heraldry of

France. The location of this art deco lion and shield composition may be found

at 1233 North Wells Street (architect unknown, c.1930)

It was believed in

some circles that the king of hearts in a deck of playing cards represented

Charlemagne (742-814), King of the Franks and ruler of much of Western Europe.

Card playing, a popular American pastime especially since the Gilded Age,

involved observing and, in fact, confronting the crowned heads of Europe with

each deal. This cultural phenomenon also occurs while observing Chicago

architecture; one is often confronted by a variety of medieval potentates while

simply passing by a decorative entrance. Any number of “architectural” kings

may resemble the image of this king of hearts. Image, c.1945, courtesy of Brown

& Bigelow. Collection of the author.

This hand-colored

English print dates from 1835 and is entitled History of Fashion. The two figures on the left don costumes worn

during the Capetian period, a dynasty otherwise known as the House of France;

these clothing styles date from 1000 to 1364. On the right are two

Carolingian-period (French) figures clothed in garments common to the ninth and

tenth centuries. Some architectural figures produced in Chicago during the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries mimic these garments with special

attention given to the headwear. Collection of the author.

Dating from 1842,

this hand-colored English print displays a French guard and is entitled Medieval Soldier. Though arguably

feminine in appearance—a Joan of Arc figure or a participant in the Children’s

Crusade?—this soldier appears ready to do battle. The soldier holds an armory crusader sword of the eleventh

century, a weapon that resembles a cross when pointed downward. The soldier’s

helmet was labeled a kettle hat, a

steel helmet usually worn by members of the infantry; its wide brim protected

the wearer from projectiles shot or dropped from above. Chicago’s soldiers and

guards carved in stone and terra cotta were based on similar prototypes.

Collection of the author.

Styles of dress for

the nobility take on a decided flair as compared to those worn by the

commoners. Garments with multiple folds of cloth are often favorite objects for

stone sculptors. Pleats and ripples, especially in limestone, lend depth and a

sense of solidity to sculpted figures through the creation of shadows. An image

like this would have aided in the creation of architectural sculpture for

Chicago buildings. Noblemen of the 14th Century is an English print dated

1842. Collection of the author.

British Kings is the title of this English copperplate engraving

dated 1814. The British royalty was always identified by a head-worn crown.

Sculpted figures of kings and queens appearing on Chicago’s buildings were

identified in much the same way. Pattern books and centuries-old images like

this one provided a resource for sculptors. Collection of the author.

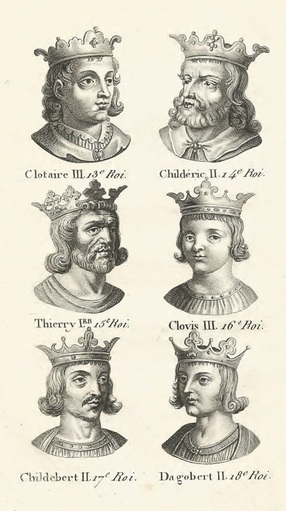

French Kings is the title of this British-produced copperplate

engraving dated 1814. The variety of royal head ware is striking, a fact not

lost on the carvers of royal heads appearing on Chicago’s more prominent

buildings. Collection of the author.

Heraldry, based upon

Medieval European precedent and found throughout Chicago, was often fashioned

of polychrome terra cotta. In this instance, a shield bearing a castle—though

stylized, this is the quintessential castle image—complete with two battlemented

towers, a grouping of three windows (a Christian reference to the Trinity), and

a raised portcullis, signifies much. As one may imagine, a castle centered in a

“heraldic field” indicates that this is a place of safety, protection, and

permanence. Location: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company - Calumet Plant, 350

East Cermak Road. This industrial-Gothic “castle”, once an immense printing

plant, was designed by noted architect Howard Van Doren Shaw (1869-1926) and

constructed between the years 1912 to 1924.

A medieval-style

terra cotta shield bearing the numbers “1349” may be interpreted either as a

memorial or a random number string. Europe then was vulgar, anti-Semitic, and

victimized by the Black Death. The meaning of the

calligraphy, perhaps runic in origin, remains elusive. Location: R. R.

Donnelley & Sons Company - Calumet Plant, Howard Van Doren Shaw architect,

completed 1924, 350 East Cermak Road.

Three small

escutcheons vie for attention on this field, rivaled by a division banner said

to be in party per bend sinister,

that is, the dividing from upper right to lower left. These motifs and arcane

definitions all harken back to medieval Europe and have strict rules for the

placement, treatment, and color of shield-included elements. Location: unnamed

commercial building, architect unknown, completed c.1925, 536 North Clark

Street.

Slithering dragons similar to this were real

to the people of medieval Europe. Some believed that it would take all the

king’s horses and all the king’s men to slay such a beast—of course with the

help of heavy armor and God’s grace. Sheridan Plaza Apartments, Walter W.

Ahlschlager architect, completed 1920, 4607 North Sheridan Road.

This tympanum

carving has all the medieval based symbols, all the bells and whistles, to rate

it one of the most engaging in the city. Two angry beasts—lion figures?—classified

as vegetable hybrids with scaly, foliate bodies, face each other in a typical rampant pose. The heraldic crest is

quartered and displays a charge, an

herb—similar to the garlic plant—as protection against evil spirits. The

crown’s design was borrowed from those worn by English counts or earls.

Bellflowers, fruits, and leaves also figure in this delightful

medieval-inspired composition. Location: 1629-1631 West Juneway Terrace, completed

c.1915, architect unknown. Material: terra cotta.

|

This forest dwelling

dwarf appears to be in quite a predicament. Will the young maiden assist?

Situations and figures like these were common in medieval folk lore, and in

American nineteenth century children’s stories. These situation comedies also

appeared sculpted on Chicago buildings. Image 1883. Hours in Fairy Land, From Grimm, McLoughlin Brothers, New York.

Copyright 1883. Collection of the author.

Romantic imagery

such as this was prevalent in literature—and in architecture, too. Horses

appearing with riders are more prevalent as park statuary rather than as façade

decorations, but the devotion to romantic imagery often remains. Architects and

sculptors responded accordingly. Image 1883. Hours in Fairy Land, From Grimm, McLoughlin Brothers, New York.

Copyright 1883. Collection of the author.

This image portrays

a rather cherubic-looking knight slaying a dragon, an old but cherished

beauty-and-the-beast tale. These stories were not wasted on Chicago folk of the

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; building façades featuring knights,

armor, castles, swords, and shields conjured up all sorts of images for

observant pedestrians. Image c.1905. HWB

Ser. 774, Germany. Collection of the author.

Medieval costumes and headdresses appear upon many of the figures portrayed on the façades of Chicago’s buildings. Accuracy was important, whether executed in stone or terra cotta. Medieval and more contemporary sources were consulted for appropriate clothing when “dressing” sculpted building figures. The very accoutrements shown here appear on many figures portraying medieval townsfolk. Image 1907. Series J3003, Germany. Collection of the author.

This carving of an English commoner of the

twelfth century is one of the oldest exterior carvings on public view

in Chicago. This gifted relic, whose origin was London’s Houses

of Parliament (Barry and Pugin, 1860’s), was executed in a richly colored, relatively easy to

carve limestone quarried in the village of Anston, South Yorkshire. It originally faced the Thames River,

but it now rests near the corner of North Michigan Avenue and Illinois Street

on the façade of the Tribune Tower Addition (John Mead Howells,

1934).

In the medieval

world of heraldic symbols this beast was referred to as a lion rampant. The old French term rampant means “rearing up,” and that is exactly what attitude, or stance in heraldry, this

lion is taking. Characteristics include the feline depicted in profile and

standing erect with forepaws raised; the position of the hind legs varied

depending upon local custom. This cameo lion

rampant image is of a female—a genuine anomaly. Symbolically the

lion-with-mane image of a heraldic shield signified strength and unbridled

courage for its protected bearer. Location: Columbia College Residence Center,

originally Lakeside Press Building, 731 South Plymouth Court, Howard Van Doren

Shaw, 1897.

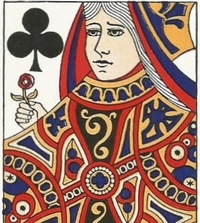

The invented medieval figure “Argine,” it was believed, was the model for the queen of clubs in a deck of playing cards. “Argine” is the anagram of “Regina,” the Latin word meaning “queen.” In popular culture, legendary and mythical figures may be interpreted through anonymous architectural sculpture—and playing cards—with varying degrees of accuracy. In this unique case, Lady Argine possesses the same countenance and simple beauty as the royal figure adjacent to a residential entrance on Waveland Avenue. For decades, images of kings, queens, and a host of European royalty were given ample opportunity to inundate Chicagoans on their buildings’ façades and during their poker nights. Image, c.1945, courtesy of Brown & Bigelow. Collection of the author.

The entertaining image, British Jesters, depicts silly people

of the Middle Ages doing silly things. Images like this one can be found on the

façades of Chicago buildings, especially theaters, also as elements of

entertainment. This hand-colored English print dates from 1842. Collection of

the author.

Military Habits: Medieval Soldiers is a drawing that depicts three

typical uniforms worn by infantry soldiers. The individual on the left wears

chain mail, a “kettle hat,” and, for added protection, holds a shield featuring

a party per bend design. The soldier

on the right is protected by an armet,

chain mail, and an armory crusader sword. The soldier in the middle needs more

equipment but appears patient. This English-produced, hand-colored print is

dated 1842 and recalls a few of the figures still surviving upon the walls of

some Chicago buildings. Collection of the author.

This polychrome terra

cotta panel recalls with accuracy the heraldry of medieval England and France.

Two griffins, symbolic of vigilance, vengeance, and wisdom, frame a shield and

a medieval war helmet—this type being an armet—a

steel headpiece with a movable visor. The predatory monsters are said to be in

the combatant rampant position, alert

and in profile facing each other. Location: 3248 North Lincoln Avenue,

architect unknown, c.1925.

Medieval shields were

sometimes divided, or marshaled, to

display two coats of arms. Marshaling in heraldry expressed an alliance between

two families or clans, or due to various social mergings. The type of

marshaling employed here is referred to as impalement,

wherein two coats of arms are retained intact and without distortion, each

occupying one-half of the shield’s field. The significance of the charges (figures in the field)

emblazoned on this terra cotta shield are puzzling to contemporary Chicagoans

but make for stimulating inquiry. Location: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company

- Calumet Plant, Howard Van Doren Shaw architect, completed 1924, 350 East

Cermak Road.

To the people of the

twelfth century, a chevron—more specifically and in this case a party per chevron in the science of

heraldry—with three wooden sculptor’s mallets, identified that this was the

emblem of a mason, a town’s master craftsman. It once signified that a builder

or mason had accomplished work of “faithful service” for the good of the

townsfolk. Location: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company - Calumet Plant, Howard

Van Doren Shaw architect, completed 1924, 350 East Cermak Road.

Dragons like this one were believed to inhabit the forests of England, indeed most of Europe, during the twelfth century. Perched atop a skyscraper, this terra cotta beast seems to be at home as a frightening, urban-dwelling monster. Sheridan Plaza Apartments, Walter W. Ahlschlager architect, completed 1920, 4607 North Sheridan Road.

Medieval shields bearing mystical and

mysterious emblems were favorite decorative props employed by architects to

complete the illusion, the pretense, embraced by Roaring Twenties’ apartment

dwellers that they indeed resided in mini-castles. The meanings of these unique

limestone shields remain as elusive to Chicagoans today as they were a century

ago. Some of the designs appearing upon a medieval-style shield may have no

historic meaning whatsoever and may be the result of the creativity of a

twentieth century architect and/or stone carver. Often artistic liberties were

taken with the authentic designs of the Knights Templar, various crusaders, and

later with the royal houses of Europe. On the other hand, some images may

indeed be accurately portrayed upon the “architectural shields” found

throughout Chicago. Location: unnamed apartment building, architect unknown, completed

c.1920, 1809 North Lincoln Park West.

A classic French

heraldic shield, featuring a single fleur

de lis, decorates the wall of a commercial building completed in 1925 and

located at 814-818 West Diversey Parkway. The other two flowers may simply be

generic floral interpretations or represent stylized poppies or daisies.

Architects Olsen & Urbain ordered these decorative elements be made of

terra cotta.

|